Ren Hang was a self-taught photographer and poet living in Beijing, China before his death at 29 years old earlier this year. Born in Changchun, Jilin Province, China in 1987, Hang went on to study marketing in a university in Beijing. He became interested in photography but seemed skeptical at first but continued to shoot until he realized that photography was his true passion. Hangs work became known through the Internet and quickly gained the attention it deserved. Although many of his websites were shut down due to their content, a new website would quickly turn up in its place.

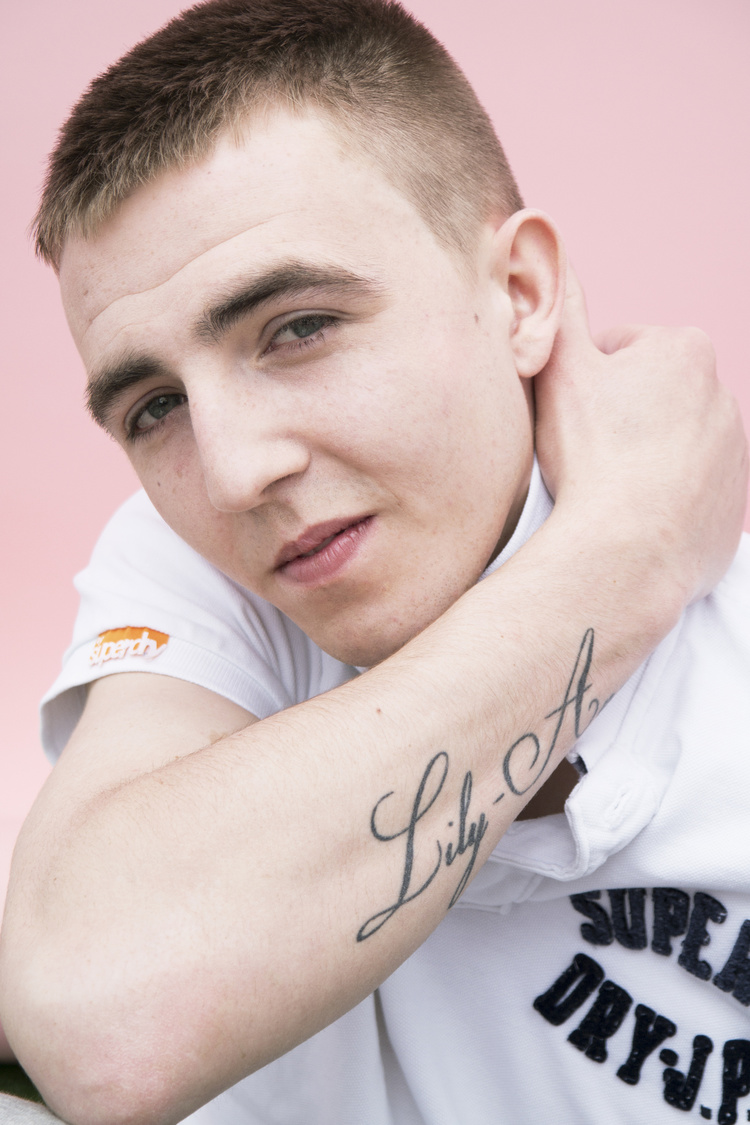

His photography mostly consisted of nude portraits of both women and men. Hang mainly shot them in his Beijing apartment, using close friends as his models. He had said that the reason he used his companions as models is because it made the shoot more comfortable for both of them. Hang insisted that all shoots must have an element of fun to them or else why bother? His type of work closely relates to the work of Ryan McGinley, a photographer who also uses friends as models in different settings that are familiar to them. McGinley is an American photographer who also creates nude portraits often in dramatic landscapes often outside in natural environments. Similar to Hang McGinley’s work also displays themes of sexuality and the body.

As Hang created these nude works in Beijing he came across many problems with the authorities over the years. In China, sex is a very taboo subject- it is never talked about openly nor displayed in public. The authorities in China are doing their very best to censor Ren Hang’s work because of the nude imagery. Hang has had many exhibitions shut down by police due to the fact that nude work was displayed. Hang has also been arrested on different occasions purely for shooting nude images outside of his apartment. Even with these restrictions in place, Hang stated that he feels most relaxed shooting in China as it is where he was born and bred.

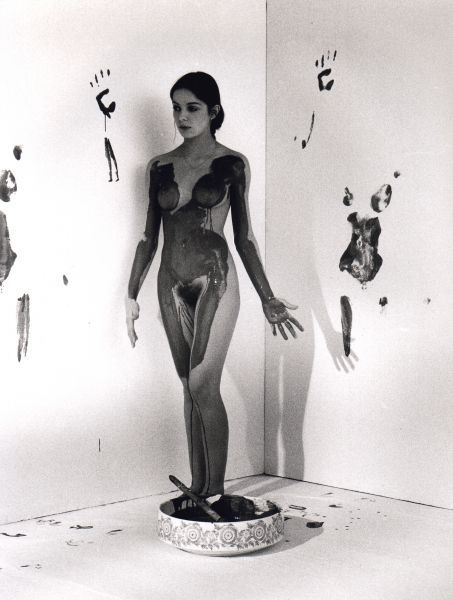

Hangs work is very focused on the body, both its shape and form. Hang likes to explore the different boundaries of the body by shooting with numerous models in a range of different poses. This work is usually shot using a 35mm film camera. A lot of the poses in Hangs photographs are very confrontational. These images force the viewer to look at these naked bodies, often giving full eye contact to the spectator. Although themes of innocence and vulnerability can be seen throughout Hangs work, there is also a strong presence of sexuality. This seems to relate back to China’s photo restrictions. These images show that even with these restrictions in place, the people of China do and will continue to talk and be open about their sexuality. Hang agreed that bodies are to be explored not hidden, and these photographs testify to that.

Despite China’s distaste with these images, Hangs work has been recognized on a global level. Having taken part in over 50 solo and group exhibitions, he is now a well-respected photographer. This work was also featured in an exhibition curated by Ai Weiwei, called ‘’Fuck Off 2’’ which opened in the Netherlands in 2013. Ai Weiwei is probably the most well known Chinese artist. Most famous for his sculptures and installations, his work attempts to bring attention to the human rights problems facing the globe.

Hangs second solo exhibition ‘’In addition to sleep’’ which was showcased from April to May in 2014 in the Vasli Souza gallery in Malmo, Sweden was a huge success. This exhibition featured some of Hangs best work. This particular body of work showed its freethinking models desire to be released from traditional Chinese values. This can be seen by the attitudes of the models, which are very matter of fact, rather than being coy. Although every image in this exhibition contains different parts of the body, they don’t in any way resemble pornographic images. Hangs photographs almost de-eroticize the body rather than eroticize the body, which is the sole purpose of pornography. This is very comforting to witness in today’s age where both women and men are constantly being over sexualized in the media.

Ren Hang successfully used different kinds of animals to draw our attention to our animalistic nature. In doing so, he showed the viewer that we have many things in common with animals and are in fact animals ourselves. By also incorporating nature and natural elements such as plants into these nude portraits this hints at the viewer to focus on the body. By bringing our attention to the body in this way it is as if we are only really viewing the body being photographed for the first time. Juxtaposed to this, often when we view traditional nude photographs we do not really take much notice of the body whereas in Hangs work this is not the case. The body now becomes more fascinating due to the use of setting and objects.

The artistic images in this exhibition are also shot and curated in such a way that these photographs almost feel like an invitation to look. The viewer does not feel ashamed or uncomfortable as one might while looking at traditional nudes because it feels forbidden.

Hangs work are mostly interiors shot in his apartment in Beijing but he did shoot exteriors in public places from time to time. Some of these images are in such amazing natural locations that they seem to be superimposed. Because of the unbelievable settings that Hang chooses often times the nude aspect of the image can seem to be using special effects. However Hang never uses any tools such as Photoshop to edit backgrounds. All of his astonishing images are authentic. Interestingly enough, Hang mentioned in interviews that at one point he did shoot landscape photographs but his fans didn’t really appreciate them and that is part of the reason why his work mainly consists of nude portraits.

Ren Hangs nude photographic works are at the forefront of Chinese as well as modern photography. In this new age of Feminist body positivity these images make an important contribution to how we view our bodies. These images are easy to access and can be found at http://renhang.org/

Words by Emma Roche

Previously published on Tribe - http://tribemedia.org/undressing-china-the-photography-of-ren-hang/